On Friday, 8th August 2025 at BIC

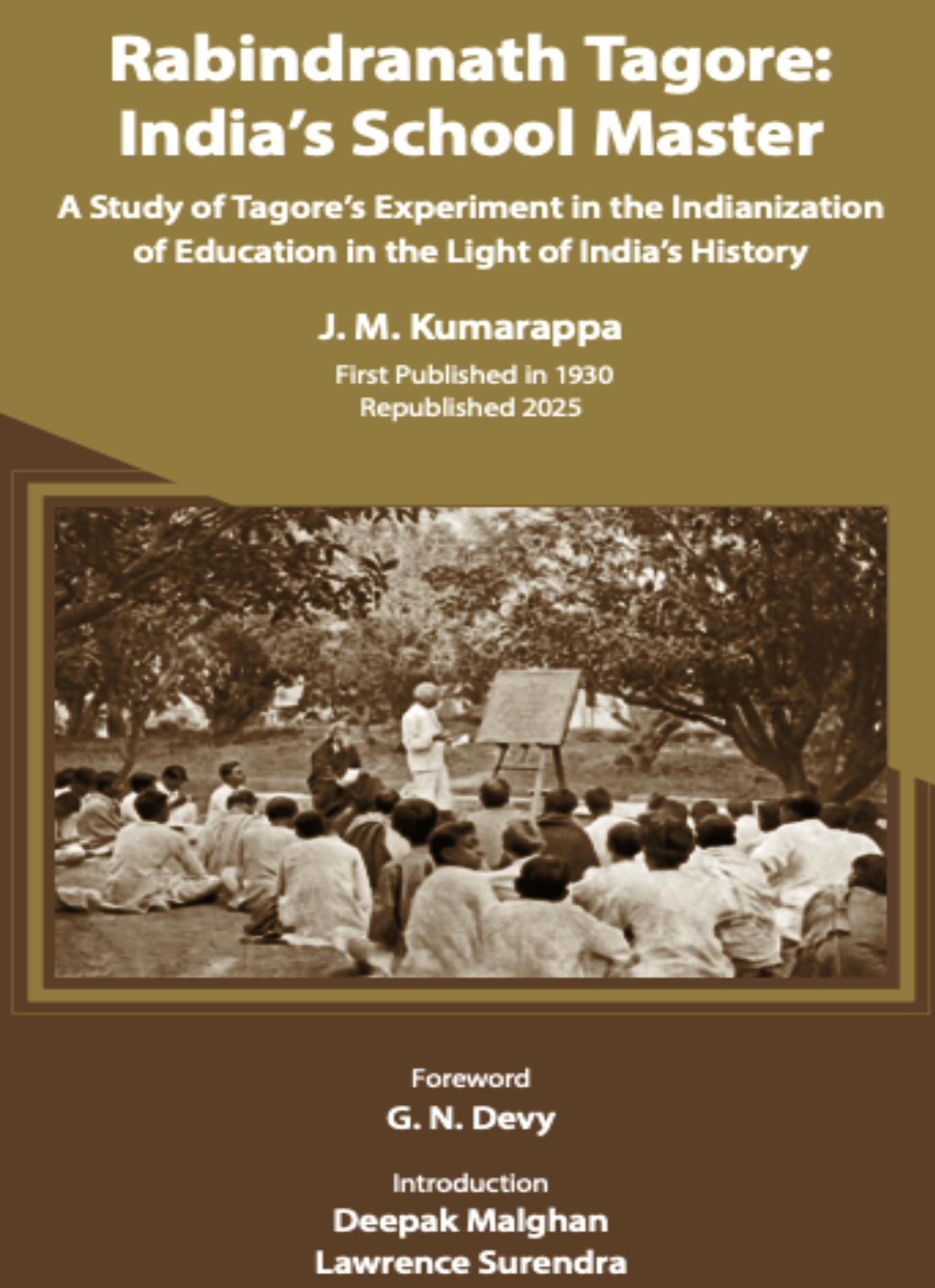

for the occasion of the launch of the book, Rabindranath Tagore: India’s School Master

Published by Earthworm Books

.

Rabindranath Tagore and Dr. Maria Montessori

Relections on the occasion

By Amukta Mahapatra

(Founder-Director, SchoolScape, Centre for Educators)

.

At the outset, I would like to thank the organisers, especially Lawrence Surendra, for inviting me to speak.

To offer my reflections on this special occasion, I will outline Tagore’s interest in education; and then some relevant facts about Dr Maria Montessori and her work with children and adults; and then look at the convergence, of what both stood for. I will be brief, as we have had illustrious speakers before and more are to follow.

I am no expert on Tagore – I have learnt from people who have been there and lived in Shantiniketan and also of course from his writings, including the Parrot’s Tale.

Tagore and Montessori knew about each other’s ideas and shared common threads of what education needs to be. They would have influenced each other surely as there was some correspondence between them.

Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for literature in 1913, as we may remember.

In 1900 itself he had started his first school, meant for children of middle-class families. He extended this idea of a school to nearby villages quite soon. He felt that children needed to grow in the midst of nature and thought that the existing school education brought to India by the British, was too much like a factory, and that it was a dead place. Children and human beings are not the same as machines he said, as each human being is unique. He felt children were ‘restless, eager and alert’ whereas the schools were ‘lifeless’, ‘dissociated from the universe’, like, ‘the eyeballs of the dead’! Being a poet, his prose itself was poetry…

So many years ago, he talked of schools as ‘factories’, which is commonly being used currently. As the earlier speaker said, ‘he was far ahead of his times and our times too’.

In 1918, he started Viswa Bharati, a University, which also had a free school on campus.

In the schools and at the university he continued with children and young people learning in the midst of nature and also felt that ancient Indian practices need to be amalgamated with modern ideas and a new education needed to be forged for a new age, for a new country. It was the times of the struggle for the British to go back, to quit India and the hopes of a new nation being formed were in the air.

With his fascination for new ideas in the spheres of his many interests and seeking out what were the frontiers of knowledge, Tagore attended in 1929, the First International Montessori Conference held in Denmark.

Dr Montessori was already well-known in Europe, in America, in Brazil in S America and in India too. She had declared with a vantage vision and an intuition in 1907, quoting a writer that the 20th Century would belong to the child.

Her first book, The Secret of Childhood, revealed the nature of the child, from her standing as a physician and having studied anthropology. It was a coming together of scientific observation and a probing heart that saw ‘the soul’ of the child in front of her. Her other book title, The Discovery of the Child’, was a true description of the times. The world discovered through her work that the child was not a miniature adult but that children had their own rhythm of life and developmental needs.

In India, along with the struggle against the British and claiming the country as its own, there was also a search for new ways of educating the young. Annie Besant, active in the political movement and President of the Theosophical Society, which ran a school or two, sent a young headmaster of the Guindy School to Europe to learn about this new method that was being talked about across Europe. Mr G.V Subba Rao (who later started and was the first headmaster of Rishi Valley School near Madanapalle, Andhra Pradesh) observed a school following this new method, met educators, attended lectures perhaps and came back with a set of materials to be replicated by local carpenters in the Olcott School run by the Theosophical Society. This was in the 20s, about ten years or more before Dr Montessori and her son came to India in 1939, which is well documented.

In 1940, Tagore wrote a letter to Dr Montessori in Madras (now Chennai) welcoming her to India and to contribute to the country’s educational ideas. He had meanwhile, set up schools called Tagore-Montessori Schools that became quite popular in Bengal and elsewhere.

To highlight a few aspects of their points of convergence –

Nature was perceived as the cornerstone for child-rearing, for both Tagore and Montessori and how ‘nature’ developed was a metaphor for how education needs to be – an unravelling and an inner forthcoming. To be in the midst of nature and be connected to it was important and that children need to listen to the trees and learn to listen to what they say is an important aspect of growing up, was one of the tenets, they both held dear.

The World Wars were an influence on both of them and they often spoke about how and why education was to be for peace and that it was the role of education to play this role actively, so that children grow up to be peaceful individuals and would promote peace in their societies.

They also had broad worldviews, not wanting to restrict children and people to the narrow ideas of nationalism but to simultaneously be world citizens.

Speaking up for political causes and putting forth new ideas for education were seen as intertwined, not as separate units. Tagore was intrinsic to the struggle for independence for the sub-continent and was involved in discussions with Gandhi, Sardar Patel and Nehru, as he spoke his mind, at times differing with Gandhi about the strategies to get there. Dr Montessori spoke up for world peace and how ‘absence of war’ was not peace. She also gave talks at women’s conferences and the need to empower women, children, as much as any oppressed human being from the shackles of the mindsets prevalent at that time. She also refused to allow her education practices to be manipulated by Mussolini and had to flee Italy and find a new home for herself and her family.

Freedom, independence, an inner discipline, uniqueness of each person and social cohesion as being intrinsic to societies and countries were the tenets they articulated in their writings and talks.

To extrapolate from the immense work each put in during their active lives till their passing away in their 80s, and available to all in the public domain, they perceived the child as a constructor, a constructor of his or her own backpack of knowledge and their personhood; not as a passive consumer. The child was not a blank slate to be written upon, a tabula rasa, or an empty bucket to be filled in by second-hand information, but capable of building their own selves in the society they were born into and the potential to create a new world for themselves and for others was a strong point made by both.

There is a lot to learn from Rabindranath Tagore and Maria Montessori, as what they brought forth and discussed, is unfortunately still relevant. Even those looking at alternative ways of schooling and learning, have not been able to crack the system that both accomplished a hundred years or so ago.

To order a copy of the book, you may send an email to earthwormpublishers@gmail.com