Mandara Learning Centre was started in early 1980, with the idea of reaching quality education to children who did not have the means to attend school full-time or regularly, especially in urban areas, where schools were available, but many of the children did not have the financial or emotional access.

Though the government schools were free, children were expected to come in a ‘proper’ dress, wear a decent pair of footwear, carry lunch to school, have a bag to carry the books that were given free, have their own stationery. Also, they could not but help their families in their daily economic activity, to earn a little more or save that bit more. Children from the fishing communities, where Mandara initially started along the Chennai sea shore, used to sit along with their mothers to sell fish, or sometimes when they got a bit older, do the sale by themselves. Some of the girls also worked as domestic help in the nearby apartments or residences. Many could not go even to the free school run by a Trust as they felt they were made fun of, humiliated for their way of dressing, their language or their behaviour, both by the teachers and students.

They were connected to the sea in front of their homes but not to the city that left them behind.

The other locality where Mandara started a Learning Centre, in 1981 was in Saidapet, where one of the biggest slum development schemes was taken up by the state government by building tenement blocks to house the poor. When we visited this area, to check out if there were children out of school, the youth association which was active and had a strong hold over the area, said that all children were going to school.

On our consecutive visits, when we pointed to a child doing errands, they said, ‘oh that boy has to support his family’. We pointed to another girl fetching water in a big pot, they said, oh she can’t read and write. She stays at home. Another day, a girl was coming back from working in a cycle repair shop, they told us that she was helping her brother! Another had hit his teacher with a slate and was thrown out of the school, many were working as domestic servants in the residential colony across the road or sweeping the district court in the vicinity or cleaning the buses in the bus depot and so on…

It was not that the youth were bluffing or trying to hide; these children were not seen as possible candidates who could go to school. They were not fit to study or even read and write.

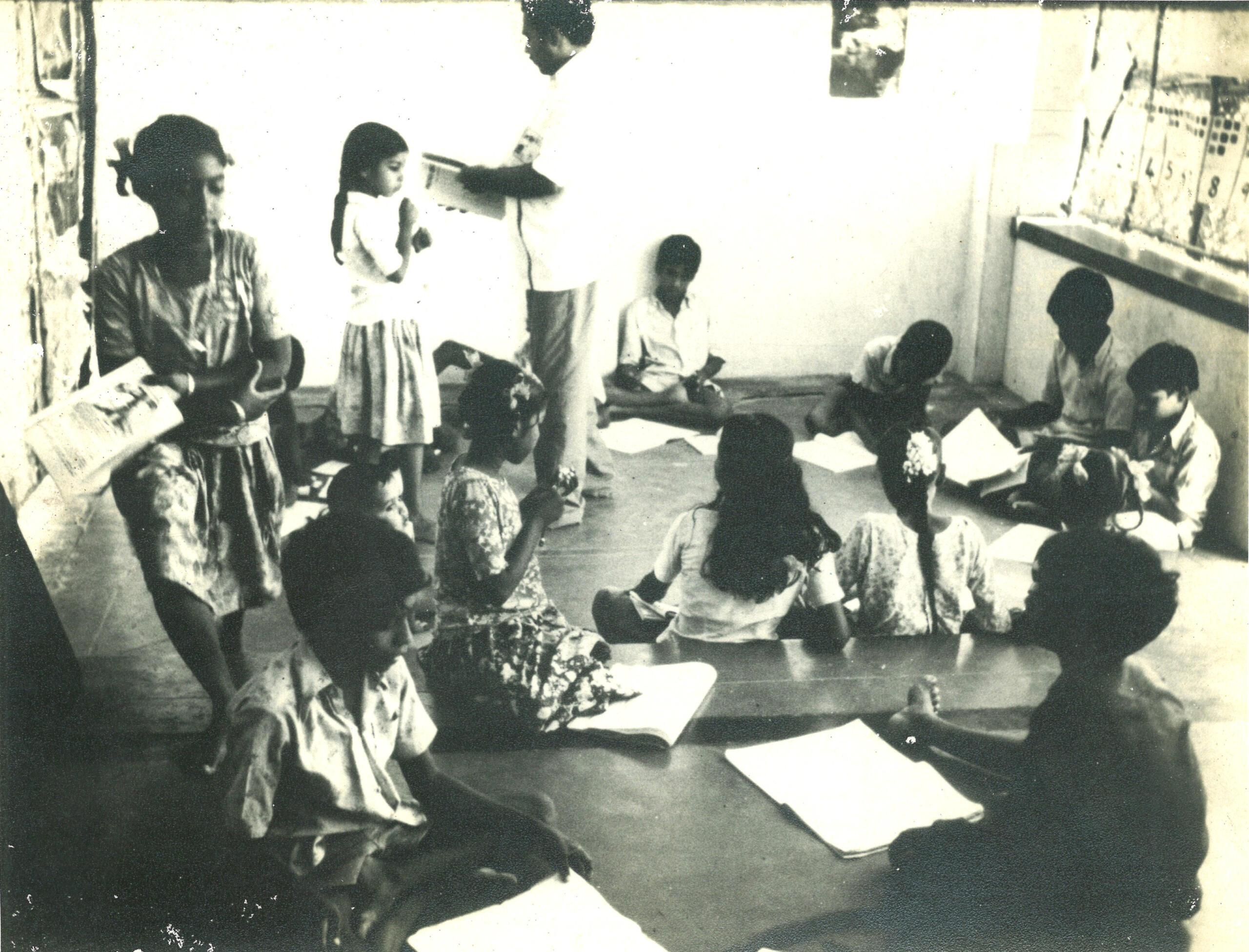

The youth club did not want us to waste our time on such youngsters but help those sitting for public exams. So, we set up, in the primary school inside the slum development zone, a tuition centre in the evenings when the school was closed. We helped them through the months prior to the examinations, to understand concepts in maths, learn English and any of the lessons they found difficult, which was almost everything in their books, as a formal Tamil was used, which was very different from the spoken language of Chennai!

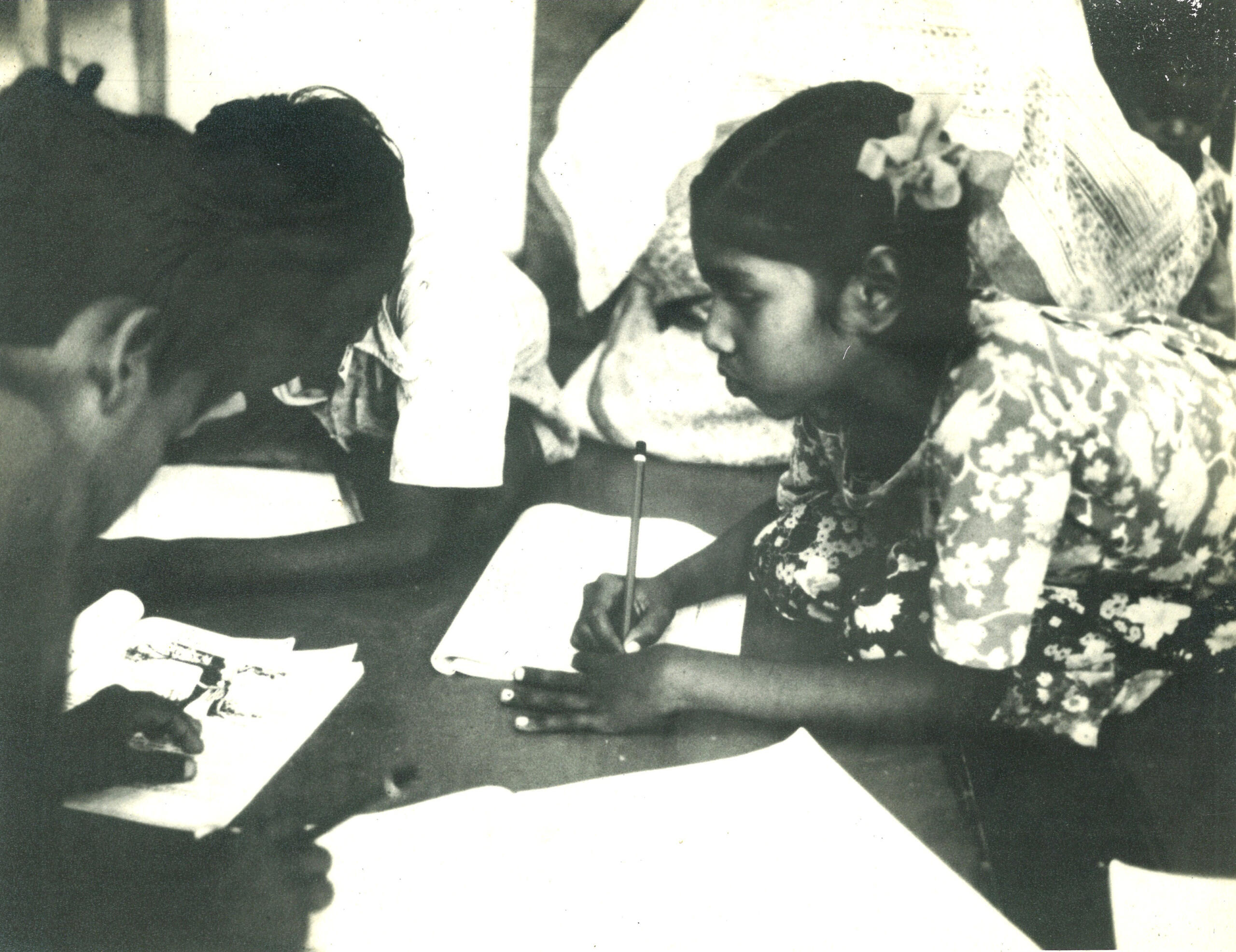

Once we built the trust of the community and the children also fared better in the exams, we suggested that we start a school for the other working children too. We rented a house and in the open garage at the back, we were ready to set up the Learning Centre. The youth club suggested which children could attend. There was no question of asking the children’s parents! The children who were mostly working asked how they could attend a school, when they were working. They found it surprising that we thought they were capable of learning. We suggested that they give up some part of their work – if they were working in three households, to give up one; if they were working in a shop, to take some time off. The timing suitable to them was in the afternoons 2 PM onwards. Both, along the coast, and in the interior of the city, in Saidapet the afternoons were convenient for them. We kept the timings to a minimum of two hours and slowly extended.

ActionAid, an international agency decided to fund the project after much discussion. It was one of the first non-sponsorship programmes that ActionAid took up. Almost all the money ActionAid received was from individual sponsors in the UK, France and Spain, who were paired with individual children through organisations in India, Bangladesh and Africa that took care of the needs of the children, be it education or health or support to their parents. The children were sponsored. Whereas for Mandara, since I was not keen on this procedure because of the situation of working children who may drop out at any time, the money was allotted to the organisation. Accounts were kept open for the community to also see, if they wanted.

To compensate the children giving up a part of their work and income, we gave the older children who were working a stipend paid on a weekly basis, far less than what they could earn. It was to enable them to learn without too many questions from their family. We also organised a snack, in the evenings, usually some kind of a protein – boiled and tempered groundnuts, channa or a mixture of puffed rice, with roasted gram and so on. They would sit together, taking turns to serve, chat and eat before they went home about 5 PM.

I had completed my Montessori course and set up an environment for the early years in a new school under the J Krishnamurti Foundation. I had also just come back after spending one and a half years in Neel Bagh, Karnataka, training under David Horsburgh. I was itching to establish a school for working children in an urban setting. Almost simultaneously, we initiated a Resource Centre for training teachers and field activists from NGOs to have new perspectives of education and learning for children wherever they were.

With financial support from ActionAid and with NFE (Non-Formal Education) being in its heyday, people came from all over India to do a month’s residential training. We were also, in turn supporting NGOs with field-based training, on-site visits and conducting workshops for those interested in school education.

At Mandara, there were two people who were responsible for the school, one academic trainer, a person engaged in documentation and small studies, a carpenter, an artist, two admin staff and a support staff taking care of security and cleanliness and I was the coordinator. The heads of NGOs we were working closely with, also dropped by, along with associates who had similar ideas on alternative education and development. Mandara became a hub for NFE in Madras (now Chennai) and for others too supported by ActionAid or by other international agencies. Discussions, debates, arguments and arriving at praxis were a continuous process.

This was from 1980 to 1984. I was 25 years old when we started. It was an adventure, a creative process of implementing and exploring further what I had learnt in the last few years, as we connected pedagogy to principles, to people, to practices, to philosophy…

Mandara Learning Centre

Mandara Resource Centre

Amukta Mahapatra

August 2023